Why is there a new race to the Moon?

December 2023 marked the 51st anniversary of Gene Cernan, the commander of NASA’s Apollo 17, walking on the Moon. His is the last footprint there; nobody has been back there since. But now, countries are vying to return.

The United States, Russia, China, and India all intend to send astronauts to the Moon by at least 2040, while China and Russia want to build a base there by 2035.

Other space powers want a piece of the action too. September saw the launch of Japan’s Moon Sniper, which is expected to touch down on the lunar surface in early 2024, while Heracles, a joint enterprise between the European, Canadian and Japanese space agencies, is due to lift off before the end of this decade, carrying a robotic rover to take samples and send them back to Earth and scout out the best location to land astronauts.

Hiscox London Market, Space Line Underwriter, Pascal Lecointe explains, “We’re in a new space race. Today’s contest is to explore the Moon’s potential wealth of natural resources, which could help us tackle the global energy crisis and climate change, as well as enable us to further explore outer space.”

“We’re in a new space race. Today’s contest is to explore the Moon’s potential wealth of natural resources, which could help us tackle the global energy crisis and climate change, as well as enable us to further explore outer space.” says Hiscox London Market, Space Line Underwriter, Pascal Lecointe

The competition to get back to the Moon is also likely to kickstart new technological breakthroughs, just as the first space race did back in the 60s and 70s. “That prompted great leaps forward in fields as diverse as telecommunications, microtechnology, solar power and water purification. It led to the invention of the laptop, heat resistant clothing, LED lights and even memory foam mattresses. It’s exciting to think what innovations this new era of lunar exploration will lead to,” says Lecointe.

What’s up there?

The Moon’s made of much more than cream cheese.

Scientists believe there are large amounts of metal oxides below its surface, as well as deposits of silicon (essential in computer chips), titanium and aluminium, whose alloys are used to make planes, spacecraft, and rockets. The Moon is also thought to have reserves of rare earth minerals, which would be vital in the expansion of green technologies, including the manufacture of wind turbines, batteries, and engines for electric vehicles, necessary for us to achieve Net Zero.

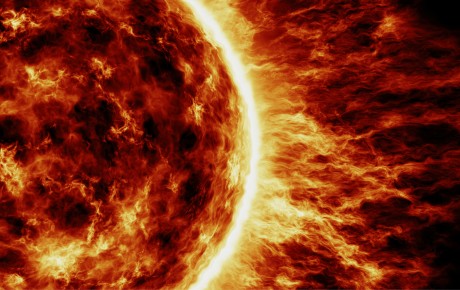

But it’s the potential to harness plentiful and clean power that fascinates and excites scientists and governments. Solar panels could work far more efficiently on the Moon, providing energy for solar bases and for us. But perhaps the Moon’s most valuable resource is Helium-3. Lacking Earth’s magnetic field, the planet is raked by the solar wind: charged particles coming from the Sun, which has left huge deposits of Helium-3. It’s widely regarded as the Holy Grail of clean energy, as it can be used to create nuclear fusion, which generates much more energy but without the harmful radioactive by-products created by nuclear fission using uranium and plutonium in reactors here on Earth.

The Moon’s reserves of Helium-3 are so rich they could "solve human beings' energy demand for around 10,000 years at least", according to Professor Ouyang Ziyuan, chief scientific advisor to China’s lunar exploration programme.

So, it’s little wonder we’re keen to explore the Moon.

We also shouldn’t overlook water. In August, India stole a march on its rivals by landing its Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft at the south pole, the first country to succeed in putting down a module there. It’s a very inhospitable place, strewn with huge boulders in rock fields as well as pockmarked by deep craters, which are the coldest places in our solar system, with temperatures of -238ºC.

But these craters could hold huge amounts of ice, which could not only supply astronauts on permanent Moon bases but be easily converted into liquid water and liquid hydrogen, the main ingredients of rocket fuel. That would make the Moon a perfect deep space garage, where a spaceship could be assembled and fuelled to fly to Mars, where SpaceX’s founder Elon Musk wants to set up a colony to make mankind a multiplanetary civilisation.

The Lunar Gateway, a space station that will orbit the Moon and be part research lab and part stopover for astronauts on their way to the Moon and Mars, is being built by NASA and a consortium of international space agencies and private contractors. “A deep space home away from home”, it will be deposited in space by SpaceX ready for the first Artemis lunar mission, scheduled for 2026.

Insuring astronomic ambitions

Countries and companies are queueing to send missions to explore the lunar subsurface, and insurance will help them reach for the Moon. Underwriters have already been presented with proposals for commercial lunar missions and for the Gateway, says Lecointe.

It might be decades since we first reached the Moon, but lunar missions remain risky. In August, Russia’s first lunar mission in half a century ended when its unmanned Luna-25 spacecraft span out of control and crashed while attempting to land on the far side of the Moon.

“Backing commercial exploration is a part of Lloyd’s DNA,” says Lecointe. “It was created in the late 1600s during the Great Age of Discovery by investors who backed entrepreneurs and fortune hunters to travel to the farthest reaches of our planet and open new trade routes. Now, we’re helping a new generation of adventurers explore outer space. It’s the same spirit but an even bigger dream.”

Cernan’s final words spoken on the Moon in December 1972 resonate as we embark on a chapter of lunar exploration. “We leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return,” he said, “with peace and hope for all mankind.”

The best space insurers understand and manage the risks that arise from man’s restless ambition to discover new places. “The Moon could help us tackle the biggest issues facing us here on Earth. The ambition to explore what’s up there is one I’d be proud to support as an underwriter,” he concludes.